Project History

My interest in what are now known as Brain-Computer Interfaces began quite a long time ago. In the 1980s, as a hobby, I was writing software for the Z80 based microcomputers like the Radio Shack (or Tandy) TRS80. One project involved a system for medical centres working with a local doctor who was a computer enthusiast as well as a senior partner in the local practice. Another project was writing a simple Shoot ’em Up game involving submarines and sea serpents!

I was impressed by the power and speed of these processors (yes, I know, but I had previously written in assembler for a large mainframe when screens were first introduced to display information in commercial systems and these microcomputers had much the same power). In the microcomputer Shoot ’em Up, for example, every time you moved any pixel on the screen, you had to look for collisions with every other pixel. That the submarine and its strings of torpedoes moved seamlessly (although blocky) was impressive to me. At around the same time, I had been reading about EEG technology and I thought that perhaps these processors would be able to analyse gross patterns in the EEG signals as well, and perhaps do something as a result.

I was interested enough to write to a university doing EEG work and float the idea. A member of the research staff wrote back saying that this would not be feasible due to the variability and non-locality of the EEG output. He was probably correct at the time, but times move on.

OpenBCI

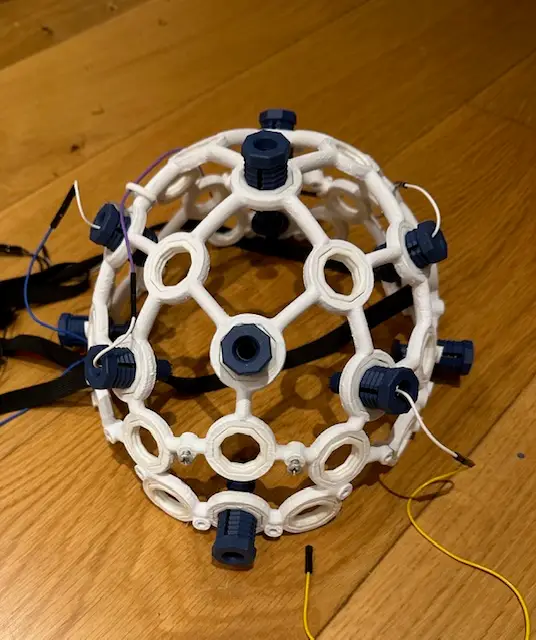

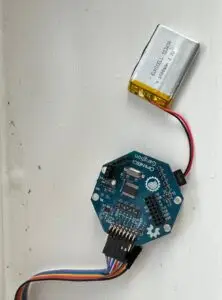

OpenBCI was formed in 2013 by Joel Murphy (hardware engineer) and Conor Russomanno (neurotechnology researcher) following a successful Kickstarter campaign. Shortly after this I became aware of the organisation and my interest in the subject was reawakened. It was awakened to the extent that I bought a Ganglion board and an Ultracortex biosensing headset

The V1KU

“The what?” I hear you ask. I had heard about this small circuit board which housed a camera and a CM1K chip. This latter device was basically a pattern recognition chip. Its storage elements were called neurons and it had 1024 of them. In fact the CM1K chips could be stacked to increase this capability, but the V1KU board had just the one. Each of its neurons had 256 slots for data, each of which could contain 256 bits. You could train it to recognise patterns in these data items. For example, the data could be an image – hence the camera – or it could be any set of data where each item is representable by 256 bits. To train it, you presented the image data or other pattern, and told it which category that belonged to. For example, if you used the camera on a alphabetic character, saved that as a image and told it which letter it was, it would store the pattern and the category in a neuron. For accuracy, you did this more than once of course. When you had finished training, you saved the data set and could put it into recognition mode. This loaded the trained data set and then, if a pattern was presented, it would check all 1024 neurons simultaneously and pull out the closest match, thus identifying the category. Clever stuff. There was no AI available at that time and writing pattern recognition software would be daunting to say the least.

I knew that the Ganglion would only provide 4 items of data, the band power at each of the 4 electrodes, and the power of each channel would have to be reduced to a 256 bit relative representation, but I thought that I could try training it and see if it did indeed recognise patterns in the power from each channel. The V1KU board was really an evaluation board. A promotional video showed these chips sorting fish into species in real time. Well I wasn’t ready to try that! You can find information on these devices on the web and read their specifications. I bought mine from a company called Cognimem but various changes in companies mean that this has changed. There is a demonstration video on YouTube if you search for V1KU Cognimem, and data sheets are available on line.

So my set up involved the Ultracortex, the Ganglion and the V1KU. I was going to try visual imagery and try to categorise a few different types of image by training the V1KU and then putting it into recognition mode. What could possible go wrong?

Software

This was where the project became difficult. The only software known to me for getting the signals from the Ganglion was the OpenBCI GU1. This displayed the processed signals in one of its widgets so it was a matter of looking at the code and seeing just where that happened. I found it was all written in Processing, a language based on Java but aimed at creatives, visual art and graphics. Suffice it to say that I was not literate in it. I knew that it would be difficult to do anything with the V1KU in that environment, so I developed a cunning plan.

Example software for the V1KU was available in a few languages, one of them being Visual Basic in the .Net environment. Not particularly compatible with Processing. The plan was to use two PCs. One would extract the Ganglion data and write it to a network file. The second would open this file and process it using a Visual Basic program which built on the Image Training example for the V1KU.

I downloaded the OpenBCI GUI source code and found a place where an array seemed to hold a packet of filtered and noise reduced data from the Ganglion. I added a small piece of code to write this to a network file with the date and time in the name so that I could process them on the Visual Basic machine in the correct order. This latter PC would open the earliest unprocessed file on the folder and then extract a figure for signal strength from the EEG packet. I did this by using the RMS of the signals. Each channel power measurement was then turned into a number between 0 and 255, attempting to preserve the relative power between the 4 electrodes. I know this ignored frequency and was just the overall power, but it was some measure of relative strength of signals between the chosen electrodes. Since I was using visual imagery, the electrodes were above the visual cortex. The four integers were presented as training data to the CM1K in the V1KU module and the class of image I was concentrating on was added as the category.

So many holes and potential flaws in this procedure. No real results. On top of that I was having great difficulty in getting the impedance of the dry electrodes in the Ultracortex down to acceptable levels. In fact I was screwing them so tightly into my skin that I caused some damage!

Gold Cup Electrodes

It’s 2018 now , 3 or 4 years since I bought the original kit. We had some other issues which meant that work on this hobby was postponed for a while. When I got back to it, I had decided that dry electrodes were one of the problems so I ordered some gold cup electrodes from OpenBCI. These would rid me of both the discomfort and the impedance issues since they used electrode paste and were attached to the skull with some micropore tape in may case. My newer PC was now Windows 10. Since Cognimem was no longer the home of the V1KU – I am not sure what the changes were in ownership – no one had written updated drivers for it. Not a serious problem since I could run that side of the software on my Windows 7 machine and the fiddled GUI on the new machine. Results were not brilliant and, in the end, I felt that this double platform was not a good idea.

Serpent & Noah the Boa

What has this got to do with EEGs and BCIs? In my case quite a lot as it happens. Remember the Shoot ’em Up game I wrote in the 80s, it was written on my first microcomputer, a Nascom 2, a single board computer probably only known in the UK. It is in a museum now! Well that game was called Serpent. You can still play it using emulators. Well I thought it would be a nice idea to update it, just as an exercise, and write it for a current platform. My grandson, Bailey, suggested Unity was a great game engine for the job. So I developed a version of Serpent in Unity. It was just for fun, not the sort of game that would interest gamers of today. That led to a further project.

When my children were small, I hand drew a book about a snake, Noah the Boa, which I subsequently updated using Corel Draw when my first grandchild was born. It was a book which featured a single continuously unfolding page. I thought it might be a nice idea to animate it using Unity and the techniques I had learnt from writing Serpent. To cut a long story short, I developed it as an app which you can now download on iPad or any Android device. Have a look at the web site Noah the Boa.

Ok, so here’s the connection to my BCI efforts. I found from OpenBCI mailshots that a talented person called Andrey Parfenov had produced a splendid software library called BrainFlow. This gave me the options of collecting data from the Ganglion and processing these signals with frequency filters, noise reduction and band power calculations using Unity and C# without me breaking a sweat. Having collected the EEG data and processed it, Unity and C# gave me the platform to present it and do anything I liked with it.

Ready to Roll

From my new found friend Copilot, I learned that success in a BCI was more likely by monitoring the Motor Cortex rather than the Visual Cortex. I was constrained by the EEG cap as to which electrode positions i could use. Across the motor cortex I only had the choice of C3, C4 and Cz. The outer ones in this band strayed into the temporal lobe. So I plumped for C3, C4, P3 and P4 since I understood that the Parietal Cortex was involved in planning movement. Hence the birth of the project in its current form.